A persistent cough, fever, and steady weight loss sent a man to his doctor. Scans revealed tumors in his lungs and lymph nodes. Everything pointed to cancer. But those tumors weren’t made of his own cells at all. Something living inside him had developed cancer first and then passed it on to him. It sounds like science fiction, but it happened. A 41-year-old man in Colombia walked into a hospital with symptoms no one could explain, and what doctors found inside him rewrote what we thought was possible in medicine. His story begins with a parasite most people have never heard of.

A Patient No One Could Diagnose

In 2013, a man in Colombia visited his doctors after months of suffering. He had a fever that would not break, a cough that kept getting worse, and he was losing weight fast. He had been living with HIV for over a decade but had stopped taking his antiretroviral medications. His immune system was weak, leaving his body open to infections that most healthy people fight off without noticing.

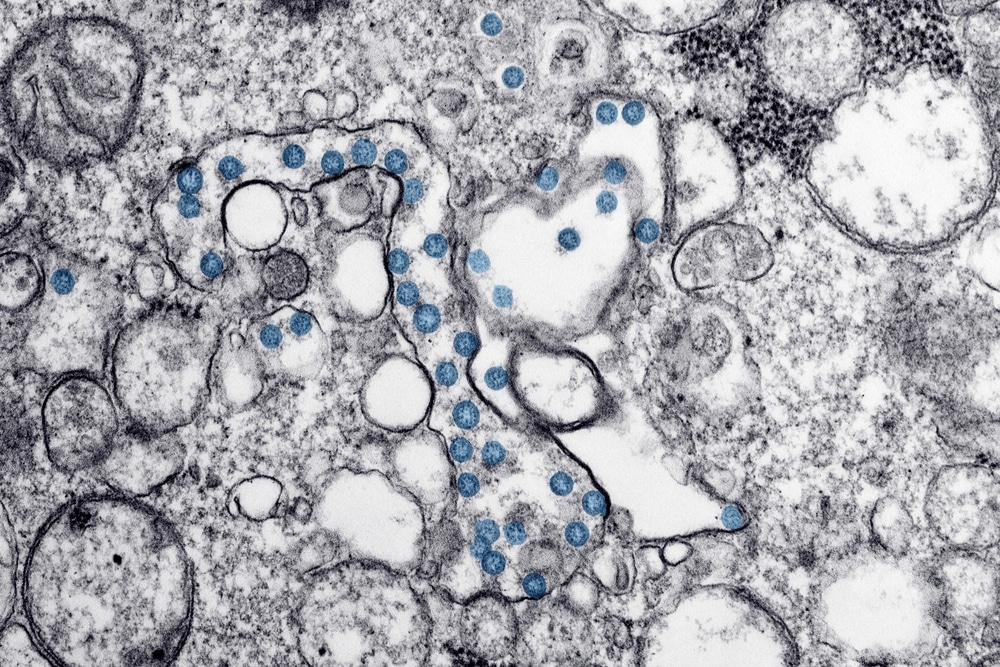

CT scans showed masses in his lungs, lymph nodes, and liver. At first glance, doctors assumed they were dealing with cancer. Biopsies were taken and sent to the lab. But when pathologists looked at the tissue samples under a microscope, something didn’t add up. Cells were multiplying fast and packing into tight clusters, a pattern you see in aggressive cancers. Yet these cells looked wrong. They were tiny, about ten times smaller than normal human cancer cells. Some were fusing, a behavior human cells rarely show.

Colombian doctors were stumped. So they reached out to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States for help.

A Nearly Three Year Hunt for Answers

When CDC researchers at the Infectious Diseases Pathology Branch (IDPB) received the biopsy samples, they faced a puzzle unlike anything they had seen before. Early lab work confirmed one startling fact: the cancer-like cells were not human. But if they weren’t human, what were they?

Researchers ran dozens of tests. They considered unusual cancers. They looked at unknown infections. Nothing fit. For months, the team worked through possibility after possibility, ruling out one explanation at a time.

In mid 2013, they got their answer. DNA analysis of the tumor tissue matched a parasite called Hymenolepis nana, a small tapeworm often called the dwarf tapeworm. Somehow, cells from a tapeworm living in the man’s gut had turned cancerous and spread through his body like a human malignancy.

Dr. Atis Muehlenbachs, the CDC pathologist who led the investigation, described the team’s reaction: they were amazed to find tapeworms growing inside a person, developing their own cancer, and spreading it to the human host.

What Is Hymenolepis Nana?

H. nana is not some exotic, rare organism. It is the most common tapeworm found in humans, infecting up to 75 million people worldwide at any given time. People pick it up by eating food contaminated with mouse droppings or insects, or through contact with feces from an infected person. Children are most often affected.

Most infected people never show symptoms. A healthy immune system keeps the parasite in check, and many carriers never even know they have it. But H. nana has a special trick that sets it apart from the roughly 3,000 other tapeworm species known to science. It can complete its entire lifecycle, from egg to adult worm, inside a single person’s small intestine. No intermediate host is needed. No complicated migration through different organs. It just keeps reproducing, generation after generation, inside one human gut.

For someone with a healthy immune system, that’s manageable. For someone with a severely weakened immune system, like an untreated HIV patient, numbers can grow fast, and the body loses its ability to keep the parasite under control.

How a Worm’s Cells Became Tumors

So, how did a tapeworm develop cancer that spread to a human? Researchers believe the answer lies at the intersection of two problems: parasitic infection and immune collapse.

H. nana has evolved ways to avoid detection by the human immune system. In a healthy person, the immune system still manages to limit how many worms survive. But in someone with advanced, untreated HIV, that defense is gone. Without immune pressure, the tapeworm population can explode.

With so many parasites reproducing so fast, the odds of genetic mutations increase. At some point, cells within the tapeworm began dividing without control, just like cancer cells do in humans. But instead of staying inside the worm, these mutant cells broke free and invaded the human host’s tissues. They formed tumors in the lungs, liver, and lymph nodes, behaving with the same aggression as human cancer, even though they came from an entirely different species.

Because the patient’s immune system was too weak to recognize or attack these foreign cells, the parasite’s cancer grew unchecked.

A Tragic Ending and Unanswered Questions

After researchers confirmed that the tumors were made of H. nana cells, they faced a new problem: how to treat cancer that isn’t human? Anti-parasitic drugs target living tapeworms, but cancer cells from a tapeworm may not respond to those medications. Human cancer treatments like chemotherapy might work, since the cells behave like cancer, but no one has ever tried it.

Sadly, the patient never got a chance to receive treatment. He passed away just 72 hours after the CDC confirmed the source of his illness.

His case, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in November 2015, became the first documented instance of a human developing cancer from parasitic cells. It raised a troubling question: how many similar cases have been missed?

Why Misdiagnosis Is a Real Concern

In wealthier countries with advanced diagnostic labs, pathologists would likely catch the size difference in the cells and run additional genetic tests. But in less developed regions, where both H. nana and HIV are common, these tumors could easily be mistaken for standard human cancer. A doctor looking at a biopsy might see aggressive, fast-growing cells and diagnose cancer without ever checking whether the DNA belongs to the patient.

Poor sanitation, limited access to HIV treatment, and a lack of advanced lab equipment create the perfect conditions for cases like this one to slip through undetected. As Dr. Muehlenbachs noted, millions of people around the world live with both HIV and tapeworm infections. More cases may exist, but go unrecognized.

What We Can Learn from a One of a Kind Case

Even though a case like this is rare, it teaches us something valuable about how disease works when the immune system fails. A strong immune system does more than fight colds and flu. It acts as a surveillance system, catching abnormal cells, whether they come from your own body or from a foreign organism, and destroying them before they can cause harm.

When that surveillance breaks down, the consequences can be bizarre and deadly. A parasite that millions of people carry without trouble became a source of lethal cancer in one immunocompromised man.

Prevention, early treatment of infections, and proper immune support matter more than most people realize. Washing hands with soap and warm water, cooking food properly, and seeking medical care for conditions like HIV are basic steps that could prevent tragedies like this one.

For travelers heading to areas where sanitation is limited, extra caution with food and water goes a long way. And for anyone living with a condition that suppresses immune function, regular checkups and open communication with a healthcare provider can make all the difference.

My Personal RX on Strengthening Immunity and Gut Health

As a doctor, I find cases like this one a powerful reminder of how connected our gut health, immune system, and overall wellness truly are. A parasite most people never notice became deadly because one man’s immune defenses had collapsed. You don’t need to fear tapeworms if you take care of the basics: keep your gut healthy, support your immune function, and pay attention to what your body tells you. Strong immunity starts with daily habits, and a well-balanced gut is where much of that immune power lives. Prevention is not complicated. Consistent, smart choices protect you from threats you may never see coming.

- Wash Your Hands Before Every Meal: It sounds simple, but hand hygiene remains one of the best defenses against parasitic infections like H. nana. Use soap and warm water, especially after using the restroom and before eating.

- Prioritize Sleep for Immune Recovery: Your immune system repairs itself during deep sleep. Sleep Max contains magnesium, GABA, 5-HTP, and taurine to calm your mind, balance neurotransmitters, and support restorative REM sleep so your body can recharge each night.

- Cook All Produce When Traveling Abroad: In areas with limited sanitation, wash, peel, or cook all raw fruits and vegetables with safe water before eating. Raw food from unfamiliar sources carries a higher risk of parasitic contamination.

- Know Which Supplements Actually Matter: Download my free guide, The 7 Supplements You Can’t Live Without, to learn which key nutrients your body needs after 40, how to spot quality supplements, and which so-called healthy choices are misleading you.

- Stay Current with HIV or Immunosuppressive Treatment: If you live with any condition that weakens your immune system, stay on your prescribed medications. Skipping treatment opens the door to infections your body cannot handle alone.

- Talk to Your Doctor About Unusual Symptoms: Persistent coughs, unexplained weight loss, or ongoing fevers deserve medical attention. Early evaluation can catch problems before they become serious, whether the cause is common or something no one expects.

Source: Muehlenbachs, A., Bhatnagar, J., Agudelo, C. A., Hidron, A., Eberhard, M. L., Mathison, B. A., Frace, M. A., Ito, A., Metcalfe, M. G., Rollin, D. C., Visvesvara, G. S., Pham, C. D., Jones, T. L., Greer, P. W., Hoyos, A. V., Olson, P. D., Diazgranados, L. R., & Zaki, S. R. (2015). Malignant Transformation of Hymenolepis nana in a Human Host. New England Journal of Medicine, 373(19), 1845–1852. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa1505892

Subscribe to Ask Dr. Nandi YouTube Channel

Subscribe to Ask Dr. Nandi YouTube Channel