A variety of factors can influence our walking speed capabilities as individuals, including lung capacity and motor control, as well as our mental health and motivation levels.

Exercise is vital for well-being and, therefore, for overall health. Any activity is great, and it’s enough to walk briskly.

If you combine walking briskly with being outdoors, you can be refreshed and calmed by the earth’s energy. With both, you are a winner!

But did you know that brisk walking can slow down your biological aging process? Biological age essentially means how worn out the body’s cells are getting.

Studies on Walking Briskly for Slow Aging

A study by Leicester-based researchers revealed that a lifetime of walking at speeds above an amble could mean the equivalent of being 16 years younger – cellularly speaking – by middle age. (1)

The study aimed to investigate the association between self-reported walking pace and leukocyte telomere lengths (LTL) – one of the biomarkers that scientists can use to assess the rate at which the human body gets older.

A previous study revealed that brisk walking can increase life expectancy by as much as 20 years, and this longer life expectancy can be achieved with a daily walk of only 10 minutes. (2)

Although it was previously shown that walking pace is a very strong predictor of health status, scientists have not yet confirmed that adopting a brisk walking pace causes better health.

Most human studies to date have been small, with some studies showing weak or inconsistent associations. (1)

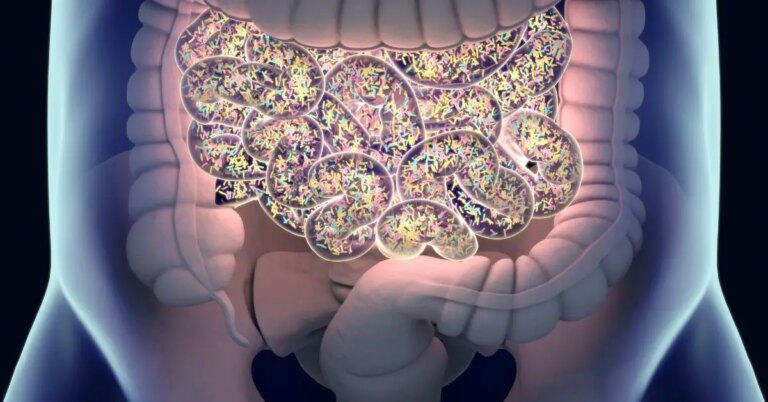

What Is a Telomere?

A telomere is a repetitive DNA sequence found at the end of a chromosome. It protects the ends of chromosomes from fraying or tangling, acting as a “brake” on cell division. (3)

In other words, telomeres work the same way as the protective tip of a shoelace. They protect the end of each chromosome from damage as they hold repetitive sequences of non-coding DNA.

Telomere shortening has been linked to aging, geriatric conditions, and mortality.

Research has shown that telomeres can also be shortened more speedily by a lack of sleep, demanding jobs, and the stresses and strains of childbirth. (13)

How the Longevity Study Was Conducted

The analysis used data from the participants within the UK Biobank, a large cohort designed to support biomedical analysis. They focus on improving the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic disease through phenotyping and genomics data. (4)

Researchers from the University of Leicester at the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) studied genetic data from 405,981 middle-aged UK Biobank participants.

They used information contained in people’s genetic profiles to show that a faster walking pace is likely to lead to a younger biological age — as measured by telomeres.

The researchers gathered individuals living within 25 miles of one of the 22 study assessment centers located throughout England, Scotland, and Wales. They provided comprehensive data on a wide range of demographic, clinical, lifestyle, and social outcomes between March 2006 and July 2010. (1)

Further, the researchers tapped into the UK Biobank database and pulled records on middle-aged individuals. Movement intensity on walks was measured by self-reporting and fitness tracking wearables worn by the people involved in the study. (1)

The Fast Walk Findings

The genetic analysis suggested a causal link between brisk walking and LTL, regardless of other physical activities. It was discovered that the steady/average and brisk walkers had significantly longer LTL compared with the slower walkers.

The brisk walkers were slightly younger, less likely to smoke, and less likely to be on cholesterol/blood pressure medications, have a chronic disease, or have mobility limitations.

The slow walkers reported less physical activity, a higher deprivation index, and a higher prevalence of obesity compared to average and brisk walkers. (1)

Conferring that brisk walking has many physical, mental, and social health benefits with minimal adverse effects, the general opinion from the researchers is that a brisk walking pace does cause overall better health.

It was concluded that a level of fervor is critical: a leisurely stroll does not seem to have the same impact (although any kind of movement is good for you). (1)

For general guidelines on health promotion, some physical activity is better than none, yet more physical activity is better for optimal health. This is hoped to provide a new recommendation on reducing sedentary behaviors for World Health Organizations. (12)

We live in a culture obsessed with constant production, consumption, growth, and doing. It’s good to do something for yourself, and through brisk walking, you have a daily opportunity to stay younger for longer.

Sign up for Dr. Nandi’s Newsletter to stay informed about recent studies with positive findings. Think blood glucose levels, low carb programs, diabetes, and slowing down aging.

Thoughts About Walking Pace

The freedom and excitement of brisk walking for humans encompass both staying young and the realization that true sources of happiness and health can come from simply putting one foot in front of the other.

The lead author of the study, Dr. Paddy Dempsey said, “This suggests measures such as a habitually slower walking speed are a simple way of identifying people at greater risk of chronic disease or unhealthy aging, and that activity intensity may play an important role in optimizing interventions.”

He added, “For example, in addition to increasing overall walking, those who are able could aim to increase the number of steps completed in a given time, e.g., by walking faster to the bus stop. However, this requires further investigation.” (1)

At the end of the day, walking outside is free!

Likewise, you can inexpensively learn powerful concepts about exercise, human nutrition, and health-promoting habits by signing up for Dr. Nandi’s Newsletter.

My Personal RX: How to Slow Down Your Internal Biological Clock

Your internal biological clock within your cells reflects the aging state of your body. This is called your epigenetic clock, and it can be changed.

Scientists have suggested some tips to slow down the aging process:

- 20 mins of exercise a day can improve your telomere length. (6)

- Improve your neuroplasticity through mental training exercises, such as playing video games, painting, or learning new skills. (7)

- Adults who get enough sleep — seven to eight hours a night — have longer telomeres. (8)

- Those who feel connected to their friends, family, and community may experience improved longevity. (9)

- Focus on whole foods and emphasize a plant-based diet. When it comes to aging-related ingredients like alcohol, red meat, processed meat, and sugar, consider ways to eliminate or lessen them. (10)

- B vitamins are also important for cell metabolism, especially Vitamin B6; therefore, supplements may help. (5)

- Take my Men’s and Women’s Core Essentials Supplement Daily and optimize your health and wellness by downloading my free comprehensive 50-page step-by-step Protocol guide.

Early changes in our lifestyles are far more effective than any remedial efforts for end-stage diseases or conditions associated with aging. We all have the power to influence our cellular health, and we can all learn how to slow down the aging process. (11)

Sources:

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-022-03323-x

- https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/S0025-6196(19)30063-1/fulltext

- https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Telomere

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30305743/?dopt=Abstract

- https://kids.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frym.2022.707514#ref4a

- https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/40/1/34/5193508

- https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2751893

- https://www.yourheights.com/blog/longevity/how-to-slow-down-the-aging-process

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3150158/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6855941/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6855941/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33239350/?dopt=Abstract

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3673231/

Subscribe to Ask Dr. Nandi YouTube Channel

Subscribe to Ask Dr. Nandi YouTube Channel