Multiple sclerosis has puzzled doctors and scientists for decades. We knew the immune system was attacking myelin, the protective coating around nerve fibers, but nobody could explain why. Now, an international team of researchers may have found the answer in a place most people would never suspect: the small intestine. Two specific types of bacteria living in your gut appear to trigger the very immune response behind MS. If confirmed, these findings could shift how we diagnose, treat, and even prevent one of the most common neurological diseases on the planet. And the story of how scientists made the discovery is just as fascinating as the discovery itself.

When Your Immune System Turns Against Your Nerves

MS is a disease where the immune system attacks myelin, the insulation that wraps around nerve fibers in the brain and spinal cord. Myelin helps electrical signals travel fast and smoothly between brain cells. When it breaks down, signals slow or stop, leading to symptoms like numbness, fatigue, blurred vision, difficulty walking, and, in severe cases, paralysis.

About 2.9 million people worldwide live with MS. Women develop the disease at rates two to three times higher than men. Doctors have known for years that certain factors raise the risk: genetics, low vitamin D, smoking, obesity, and infection with Epstein Barr virus. But none of those factors on their own could explain why the immune system starts attacking myelin. More than 200 genetic variants have been linked to MS risk, yet many people carry those variants and never get sick.

Something else had to be at play. And researchers started to suspect the answer might be living inside us.

Trillions of Bacteria and One Big Clue

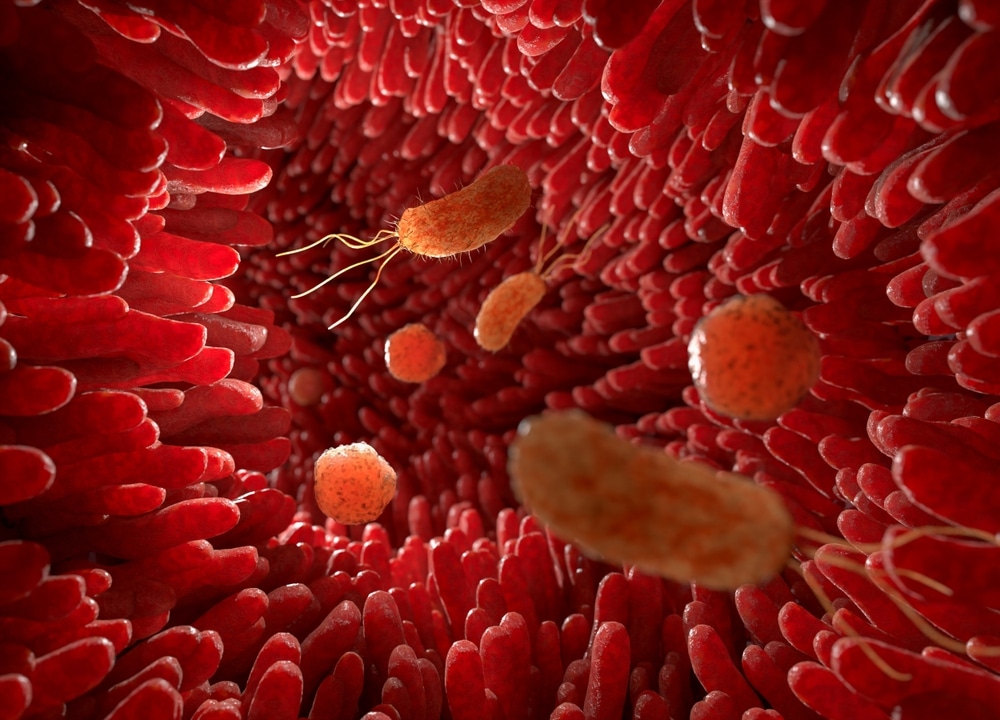

Your gut is home to trillions of bacteria. Together, they form your gut microbiome. These microbes help digest food, produce vitamins, and regulate immune responses. When the balance of your gut bacteria shifts, your immune system can shift with it.

Large population studies had already shown that people with MS carry different gut bacteria compared to healthy individuals. Researchers even found that transferring gut bacteria from MS patients into genetically susceptible lab mice could trigger an MS-like disease. But a major question remained: which bacteria were responsible?

Earlier studies had produced conflicting results. Some identified certain bacteria as increased in MS patients, while other studies found the opposite. Differences in genetics, diet, geography, and study design made it hard to pin down the real culprits. Scientists needed a cleaner approach, one that could strip away most of the noise and zero in on the bacteria that actually matter.

Identical Twins, One Key Difference

Researchers from Germany and the United States designed an experiment that was simple in concept but powerful in execution. Published in PNAS, their study focused on identical twins where only one twin had MS.

Why twins? Identical twins share nearly all their DNA. Participants in the study also grew up in the same household, eating similar diets and sharing similar lifestyles until about age 20. By comparing these genetically matched pairs, the researchers could filter out most genetic and environmental noise and focus on what was different in the gut.

From 81 identical twin pairs, the team collected fecal samples and analyzed bacterial profiles using 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Over 50 types of bacteria showed up at different levels between twins with and without MS. Several beneficial bacteria, including propionate producers like Dialister succinatiphilus and Prevotella buccae, were decreased in MS twins. Meanwhile, bacteria like Eisenbergiella tayi appeared at higher levels in the twins who had MS.

But fecal samples only tell part of the story. Most previous MS microbiome studies stopped at stool analysis, which can miss bacteria that live deeper in the gut. So the team went further.

Looking Past Stool Samples to the Small Intestine

Four twin pairs volunteered for enteroscopy, a procedure that allowed researchers to collect bacteria directly from the terminal ileum (the end of the small intestine) and the colon. Why the ileum? Because it houses the highest concentration of immune cells that interact with gut bacteria, including proinflammatory Th17 cells that scientists believe are central to MS.

Bacterial profiles differed between gut segments. Some bacteria that were plentiful in the ileum barely showed up in stool samples. Genera like Escherichia and Shigella were common in intestinal fluid but nearly absent from feces. If researchers had relied on stool alone, they would have missed key players.

Within each twin pair, bacterial profiles looked more similar to each other than to unrelated people with the same disease status. But at the genus level, differences between the MS twin and the healthy twin began to appear, especially in the ileum.

What Happened When Mice Got MS Twin Bacteria

Here is where the study got interesting. Researchers took ileal bacteria from MS twins and healthy twins, then introduced those bacteria into germ-free mice genetically prone to developing an MS-like disease called EAE (experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis).

In the first experiment using a female twin pair (one with MS, one without), the results were stark. Five out of six female mice that received bacteria from the MS twin developed disease. Zero mice that received bacteria from the healthy twin got sick. Sick mice showed paralysis, spinal cord inflammation, and damage to myelin, all hallmarks of human MS.

A second experiment with a male twin pair showed the same pattern. Mice colonized with bacteria from the MS twin developed disease at much higher rates than those receiving bacteria from the healthy twin. In both experiments, female mice got sick more often than males, mirroring the sex difference seen in human MS.

One pattern stood out across all experiments. In mice that received bacteria from healthy twins, the bacterial community stayed stable over time. In mice that received bacteria from MS twins, the gut bacteria shifted dramatically as disease developed.

Meet Eisenbergiella Tayi and Lachnoclostridium

Two bacteria from the Lachnospiraceae family emerged as the most likely triggers. In the first experiment, Eisenbergiella tayi dominated the gut of every mouse that developed disease. At the start of the experiment, E. tayi was a minor player. But by the time mice showed symptoms, it had taken over, pushing out protective bacteria like Akkermansia.

In the second and third experiments, Lachnoclostridium expanded in the same way. It started small and grew to dominate the gut of sick mice while beneficial bacterial species disappeared.

Here is a paradox the researchers flagged: both E. tayi and Lachnoclostridium exist at very low levels in the human gut. That is likely why most earlier studies missed them. One explanation? These bacteria may form biofilms on the intestinal wall, allowing intense interaction with immune tissue even though they represent a tiny fraction of total gut bacteria.

When other, unrelated bacteria bloomed in the mice (like Staphylococcus), no increase in disease occurred. Only the expansion of these two Lachnospiraceae members was tracked with MS-like disease.

How These Bacteria May Fool Your Immune System

So, how do two gut bacteria cause the immune system to attack the insulation of nerve fibers in the brain? One theory is molecular mimicry. E. Tayi and Lachnoclostridium may produce molecules that look similar to myelin components. When immune cells in the gut encounter these bacterial molecules, they mount an attack. But because the bacterial molecules resemble myelin, those same immune cells travel to the brain and spinal cord and attack the nervous system by mistake.

Mice colonized with MS twin bacteria showed higher levels of Th17 cells (proinflammatory immune cells) and lower levels of regulatory T cells (immune cells that keep the system in check). Th17 cells are known to get activated in the small intestine and then migrate to the central nervous system. When regulatory T cells decrease, there is less braking power to stop the immune system from going after the body’s own tissues.

An alternative theory: these bacteria may not trick immune cells directly but instead create a gut environment that activates autoimmune T cells through metabolites. Either way, the result is the same. Immune cells leave the gut primed for attack and head straight for myelin.

What Could Change for MS Patients

If future studies confirm these findings, the implications are significant. Doctors could one day screen for E. tayi and Lachnoclostridium as early biomarkers of MS risk, long before symptoms appear.

Treatment could shift from broad immune suppression toward targeted microbiome modification. Imagine therapies that reduce specific harmful bacteria without wiping out the rest of your gut. Targeted antibiotics, bacteriophages (viruses that kill specific bacteria), or carefully designed probiotics could all become part of the MS treatment toolkit.

For organ transplant patients and people with other autoimmune conditions, similar microbiome-based approaches could reduce the need for drugs that suppress the entire immune system.

Researchers are honest about the study’s limitations. Only a small number of twin pairs underwent enteroscopy, and results from mouse models do not always translate directly to humans. More studies, especially clinical trials in people, are needed before these findings become treatments. But as a proof of concept, the results are strong. Two independent twin pairs, multiple experiments, consistent bacterial patterns, and clear disease outcomes in mice all point in the same direction.

My Personal RX on Supporting Gut Health and Immune Balance

As a doctor, I find this MS research exciting because it confirms what many of us have suspected for years: gut health and immune function are deeply connected. Your gut bacteria do far more than digest food. They communicate with your immune system every single day, and when that communication breaks down, the consequences can be serious. MS affects nearly 3 million people worldwide, and knowing that specific gut bacteria may trigger the disease opens an entirely new door for prevention. You do not have to wait for a clinical trial to start protecting your gut. Simple daily choices around food, sleep, stress, and supplementation can keep your microbiome balanced and your immune system working for you instead of against you. Here is what I recommend.

- Eat More Fiber-Rich and Fermented Foods: Vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and fermented foods like yogurt, kimchi, and sauerkraut feed beneficial gut bacteria and help crowd out harmful species.

- Move Your Body for at Least 30 Minutes a Day: Regular exercise lowers inflammatory markers in the blood and promotes a healthier, more diverse gut microbiome.

- Prioritize Sleep Every Night: Poor sleep disrupts gut bacteria and weakens immune regulation. Sleep Max combines magnesium, GABA, 5-HTP, and taurine to calm your mind, balance neurotransmitters, and support deep, restorative REM sleep.

- Know What Supplements Your Body Needs: After 40, nutrient gaps affect energy, immunity, and sleep quality. Download my free guide, “7 Supplements You Can’t Live Without,” to learn which supplements matter most and how to tell quality products from junk.

- Reduce Processed Foods and Added Sugar: Both promote inflammation and feed harmful gut bacteria at the expense of beneficial species.

- Manage Stress With Daily Practice: Chronic stress raises cortisol, which disrupts the gut lining and shifts bacterial balance. Even 10 minutes of deep breathing, meditation, or journaling each day can make a real difference.

- Stay Hydrated Throughout the Day: Water supports digestion, gut lining health, and waste removal. Aim for at least eight glasses daily.

- Talk to Your Doctor About Your Family History: If MS or other autoimmune conditions run in your family, bring it up at your next visit. Early awareness gives you the best chance to act before symptoms start.

Source: Yoon, H., Gerdes, L. A., Beigel, F., Sun, Y., Kövilein, J., Wang, J., Kuhlmann, T., Flierl-Hecht, A., Haller, D., Hohlfeld, R., Baranzini, S. E., Wekerle, H., & Peters, A. (2025). Multiple sclerosis and gut microbiota: Lachnospiraceae from the ileum of MS twins trigger MS-like disease in germfree transgenic mice—An unbiased functional study. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(18), e2419689122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2419689122

Subscribe to Ask Dr. Nandi YouTube Channel

Subscribe to Ask Dr. Nandi YouTube Channel